A native yard success story

Someone recently asked me what I miss about living in Missouri. My answer kind of surprised me: bugs.

As a San Francisco resident now, I miss the humid environment I grew up in, not because I enjoy sweating profusely in the summer, but because now I know what comes with humidity. Growing up, summer meant months of mosquito bites all over my body, no matter how much bug spray I used. I don’t miss that. But the thrill of firefly chasing and the sounds of crickets and cicadas filling the background of every evening bring so much comfort.

These days, living in any city means being detached from a whole spectrum of non-human life. The idea of a loneliness epidemic has gotten a lot of attention in recent years, and research backs it up. Much of this loneliness is correctly attributed to social media, considering that loneliness among teens had been slowly declining since the 90s, but shot upward significantly after 2012 (Generations). But we’re missing something huge if the story stops there.

Species loneliness is defined by Robin Wall Kimmerer, author of Braiding Sweetgrass, as “a deep, unnamed sadness stemming from estrangement from the rest of Creation, from the loss of relationship” because “as our human dominance of the world has grown, we have become more isolated.” We have all but removed ourselves from the natural cycles of life and our fellow creatures. It doesn’t have to be this way, and it shouldn’t. Living in an urban area need not mean 90% of the species interaction you have is with begging pigeons, your neighbors’ dogs, and the occasional rat.

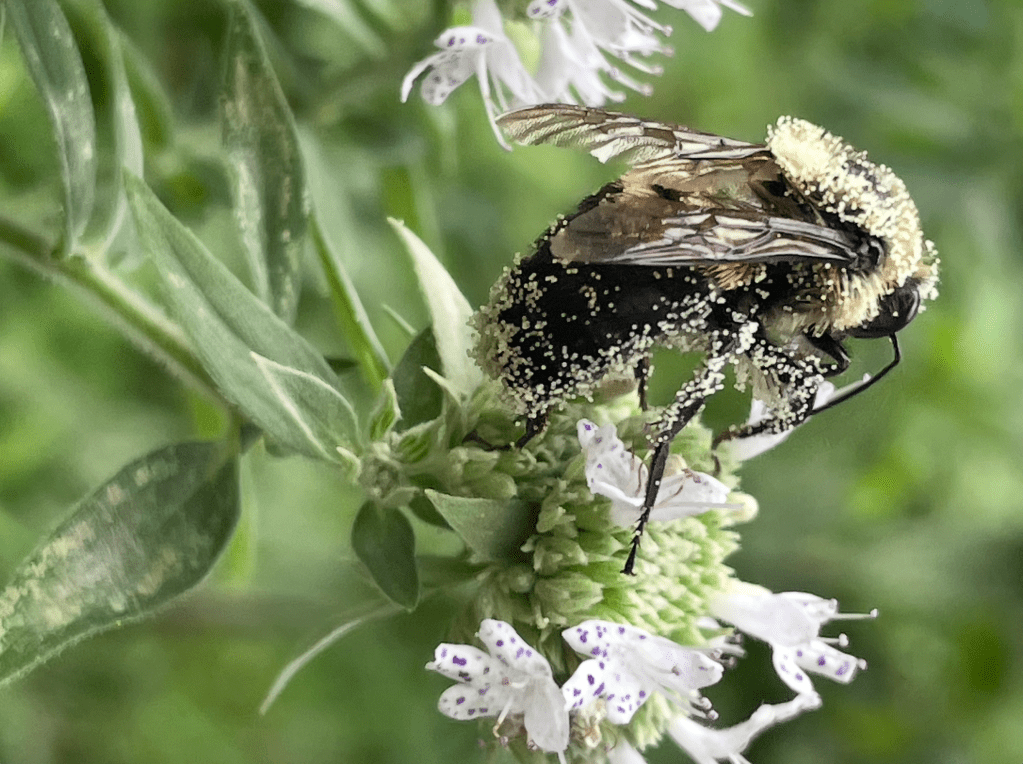

I just went home to St. Louis for a week. Home – where I was greeted by a thriving prairie in my parents’ yard. It stands a playful field of lush green, peppered with vibrant flower blooms, each plant splaying out in every direction, looking free and happy to be alive, dancing in their weird shapes and interacting with all manner of miniature life. Though my parents are empty nesters, their yard is anything but empty. It’s filled with nests of many creatures – a thriving habitat for birds, bees, butterflies, other insects, and the many beautiful native plants that shelter them. At last count, the back and front yards contain 118 native plant species. This meant I encountered several non-human lives while home, all without leaving the premises. The evening I arrived I saw a praying mantis. Thursday I saw a couple bees. Friday afternoon I saw a humming bird. I spotted countless butterflies and fireflies. Simply standing in the front or back yard at this house, it’s harder for me to feel alone.

Sitting on the front steps, I had a conversation with the naturalist behind this prairie oasis at my childhood home. My brother, Ben Thomas, who also happens to be a botanist and curator of the arid plant collections at the Missouri Botanical Garden.

This little ecosystem did not exist there just 7 years ago. Like all the best things, it started as an experiment. In 2018, Ben was working at a public park in horticulture and was starting to do garden designs there. He reached a point of frustration with how difficult it was to grow native plants or anything that looked less than perfect. That led him to want to experiment in his own yard. He recounted, “So I got really into all kinds of cool plants and I just wanted to grow them and see what happened. As soon as I planted them, all of this wildlife showed up, like bees and butterflies, caterpillars in the yard. All of a sudden, life just appeared.”

After seeing the transformation of life in his own yard, Ben set his sights on my parents’ yard. The yard we grew up with had a typical lawn, two giant square shrubs hugging our stairs, and a holly against the front of the house. Ben explained that the shrubs and the holly were native to Asia, and our native insect fauna were unlikely to be tempted to eat them (evidenced by the lack of bite marks in the leaves). “It was taking up space and not providing anything to the ecological community…So when I came back here, I was like ‘wow, what a waste of space.’” Thankfully, my parents were on board to support his vision, and Ben set out to provide a cozy home with a stocked kitchen for our area’s critters. Thus, the seed of transformation was planted – along with the seeds of many native plants. He got to work on both the front yard and the back.

At this point you might be wondering, what even is a native plant? In common understanding, a native plant is good and an invasive one is bad – a plant existing away from its home, taking resources from the native plants (kind of a disturbing rhetoric if you think about it…). I’ve only recently learned that the simplicity of framing plants as either native or invasive isn’t all that helpful. In practice, it’s more complicated than that.

Does nativeness matter? In Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer describes how some plants displaced from their original homeland assimilate to a new place beautifully – essentially, they learn to be a good neighbor. Others become invasive only when they prove harmful to the new environment by overtaking the native plants. Contrary to popular belief, most non-native plants aren’t invasive. Just like with people, it shouldn’t matter where you come from or where you ended up. Can you be a good neighbor where you are now?

Ben also pointed out that determining whether a plant counts as native is inherently slippery. There are scales of regionality – is it native to the country? The state? The municipality? Where do you stop? To Ben, it doesn’t matter so much. He cares less about a plant’s perfect nativeness than about how much it contributes to the local ecosystem. To measure this ecosystem contribution, Ben used an approach he describes as ‘ecological call and response.’ His goal was to plant native plants, then watch and see if critters liked the ones he chose. This method employs a rare humility, acknowledging that humans cannot know what other animals like, so it’s best to try stuff and let them respond by either coming or not.

Ben’s native yard philosophy is strongly directed by maintaining its usefulness as a habitat. That’s why the yard is mostly native grasses. Grass drives the prairie ecosystem because it allows for habitat year-round, enticing animal life with a reliable home, as grasses’ dried leaves provide cover in the winter months. A native yard that’s just wildflowers, on the other hand, doesn’t – in winter, they tend to drop all their leaves.

But his favorite thing about grasses? Their vast root systems. Grasses have extremely dense and deep root systems. As opposed to trees, which store carbon in their more exposed trunks and branches, grasses deposit their carbon in the soil. It’s a much more efficient way to keep carbon out of the atmosphere.

Intricate relationships

Another practice Ben is pushing back on is the individualism that has bled from human society into the way people garden. Life is a cycle of reciprocity. It prioritizes the wellbeing of the whole, a system in which all species benefit and balance is kept in check. Ben sees our native yards simply as allowing this natural cycle to run. It is a mindset of building a thriving community, caring for all the beings as evenly as possible. Not just being invested in the thriving of individual plants.

We are in the midst of a mass insect extinction, largely due to habitat loss. Because of the connectedness of life, losing insects is catastrophic not just for insects, but for the web of life, which very much includes humans. Most of our food production (75%) is dependent on pollinators. Insects also feed birds, break down animal waste, recycle nutrients, and maintain healthy soil. We must take care of the middleman. You do that by planting native plants they like because nearly all of the insects in a region are native. Ben explained, “It’s this really delicate dance that has evolved over millions of years between very specific insects and very specific plants, and those insects need those plants to grow. So if you don’t have that specific plant, you can’t get that insect.”

He gave me an example of an amazing symbiotic relationship between three organisms in the Yucatan peninsula that can’t survive without each other. Ants find their home in a specific tree. Over time, the tree evolved to produce sugar and protein sacs for the ants in exchange for the ants’ protection of the tree. In time, a species of jumping spider jumped on the bandwagon of the free protein sacs and became the world’s only known vegetarian spider. This spider can now only survive on this specific tree. Once you build the habitat, life figures out how everyone can thrive in ways much more efficient and cleverer than you could have.

All of life has evolved to be in a symbiotic relationship with one another, and an ideal native yard reflects and embraces that.

Douglas W. Tallamy, author of Bringing Nature Home: How You Can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants, agrees:

“species have the potential to sink or save the ecosystem, depending on the circumstances. Knowing that we must preserve ecosystems with as many of their interacting species as possible defines our challenge in no uncertain terms. It helps us to focus on the ecosystem as an integrated functioning unit, and it deemphasizes the conservation of single species. Surely this more comprehensive approach is the way to go.”

A changed perception of plants

The experiment mindset when growing a native garden reverberates out to other new ways of seeing the world and the creatures you are strengthening relationships with.

I think it’s hard to nurse and grow native plants, watching and closely interacting with them over the years, without developing a real tenderness towards them as beings, like Ben has. It’s obvious in the way he treats them and talks to them. When detailing the yard’s transition over the years, he affectionately likened the plants’ growth pattern to that of human teenagers. “They’re trying to figure out how to live, so the first year that they get big is like the first year a kid becomes a teenager. They’re super awkward. They grow way too fast, they grow in weird directions because they’ve never been this tall before or this large, they don’t know how to handle life very well.” They learn and grow and experiment like the rest of us.

In this open-minded relationship, you learn to see plants as imperfect, living beings, instead of flawless objects existing only for our aesthetic pleasure. You can start to genuinely view plants as your neighbors and equals when you let them live full, dimensional lives.

What’s in it for you

Ben and I spoke about the wide variety of benefits that come from planting and tending to a native yard. We both agreed that it’s better to emphasize the personal perks before the collective benefits, even though the two are intimately related and reinforce one another. The thing is, in an individualized society, collective benefits are really seen as secondary benefits. When you lead with those, something that would otherwise be exciting to do becomes perceived as a chore.

Regardless, it’s important to understand what the collective benefits are, and just how broadly they reach. If you are prone to feeling powerless in making the world a better place, you should know that building a native yard has massive positive ripple effects. Native yards use far fewer resources than turf lawns, strengthen overall ecosystem health, reduce air pollution, and improve climate resiliency by sequestering carbon, protecting against extreme heat, and absorbing rain during flood events.

Touching grass (but not mowed grass, native grass)

Touching grass is a phrase with really apt, literal meaning that resonates deeply with today’s internet generations. If someone says ‘go touch grass’ – it literally means go touch grass. It means to turn off the digital world and leave the house. To find a park or natural park, and do real things in the real world. To ground oneself in the here and now. Shocking as it may sound to older generations, a lot of social media natives really do have to be reminded to do this. The addictive nature of watching the world burn on our phones can spiral destructively for hours unless proactively interrupted. A native ecosystem accomplishes this ‘grounding’ thing very powerfully. Ben spoke of this as a very real benefit to the yard. “You can go read the news and be like ‘Jesus f-ing Christ, now we’re at war, that’s wonderful.’ You know? It’s dark. And then you can go outside and be like ‘oh look, a butterfly!’ It’s very therapeutic.”

Native yards also allow so much opportunity for play. One of my hobbies is photography. There’s nothing better than simply walking outside with my camera when I’m home, and getting to capture a new moment. I know there will be something dynamic, fresh, and different every time I step into the yard. The ever-changing light interplaying with the myriad of leaf, stem, and flower textures, the funny angles of the quirky plant shapes, and of course, whatever creature happens to be visiting or feeding for me to spy on. The yard is an endless source of beauty and inspiration. You can customize your native yard to enhance whatever your hobbies are, whether that’s photography, bird watching, floral arranging, or design [insert yours here].

Thanks for reading Clarity in Catastrophe! If you liked this post, please share it to help spread the word.

You can support independent writing and art by subscribing to my Substack and engaging with my posts. Thank you!

Leave a comment